Hear Me Now

an ekphrastic poem addressed to an unknown, enslaved potter. Also some thoughts on the life and work of Dave the enslaved potter/poet who signed his work and decorated it with short poems .

Hear Me Now

______________________________

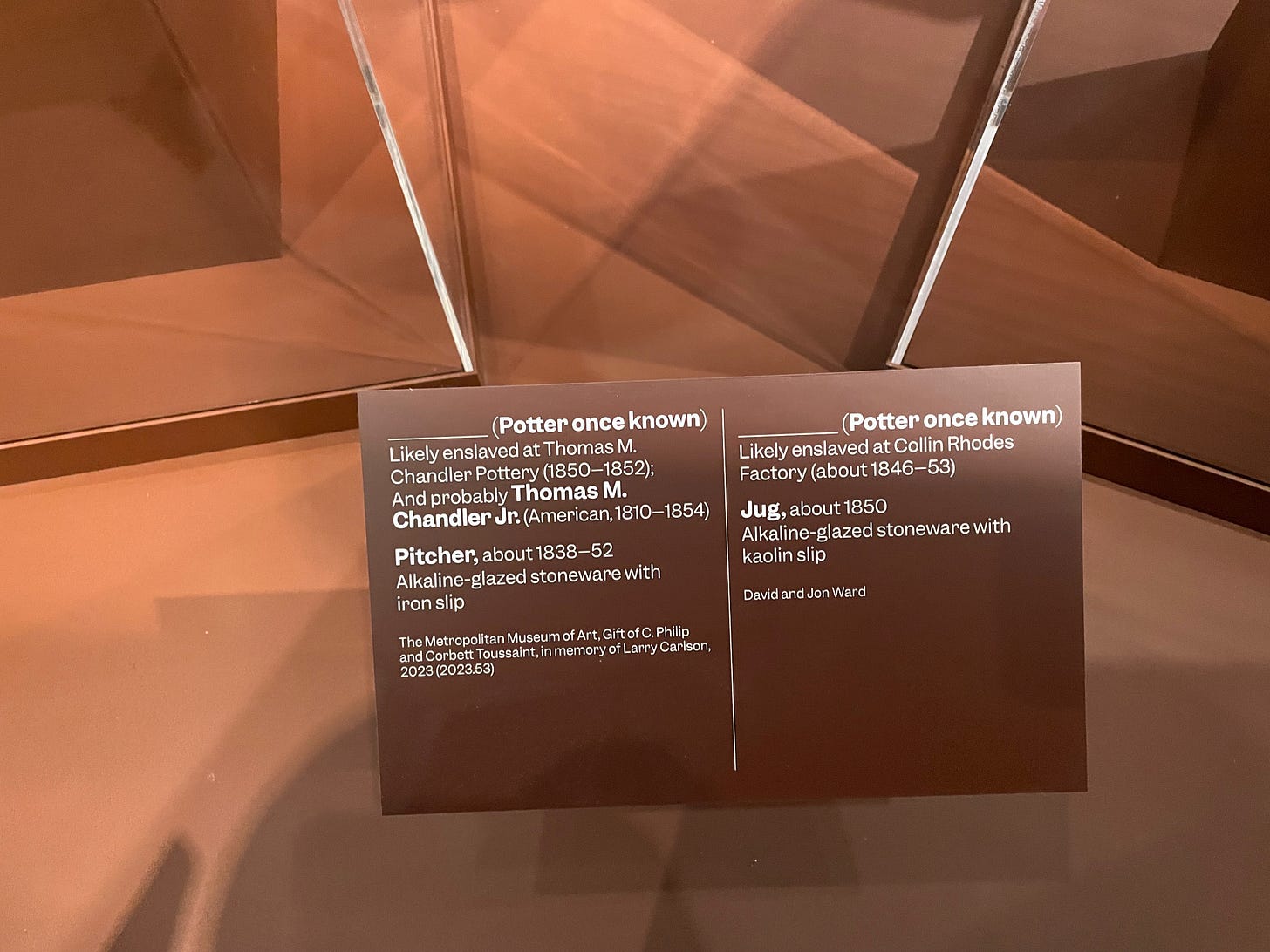

There is a blank line on the brown

placard where the maker's name should

rightfully sit. An eloquent line

holding a place, marking a vacuum,

an incalculable loss.

(Potter Once Known) in parentheses

Likely enslaved at...

The curator was a poet of restoration, working

with space and

time, bringing us to the place

Where once everyone knows

the name of the person

whose skillful hands danced

this piece of earth into shape

and whose wise mind breathed its form

into being, who knew the secrets

of clay and slip and glaze, the transforming alchemy

of fire. Who

(who? who?)

delighted in texture, in flourish,

in rhythm, in dance of body, in dance

of lines on curving form--

strong yet fragile and full

of grace.

Oh how I long to see your face

and know your name. To see

your eyes and hands sparking, O fellow

poet, maker, imago dei imaging forth

the great Potter's work in your

daily toil, with joy and sorrow, grief and gladness

pain and pleasure— lost and gained in time.

You are not lost to human memory,

Oh Once-Known-Potter; but here we

have made a place to remember

that once you created with earth

and water, with fire and breath and

flesh this still-dancing ballet of

space, embracing emptiness. Your

name hangs in the dark silence at

the bottom of the jar. If we listen

perhaps we can hear its wings

rustle restlessly, the faint echo

caught forever that ears cannot

catch nor eyes know. But heart

guesses— almost. Almost. AlmostThe Black Potters of Old Edgefield

This ekphrastic poem was inspired by an exhibit I saw at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 2023, Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina. Specifically inspired by the curator’s notes1 which listed a blank line and (Potter once known) for many of the pieces.

This exhibit had pieces that fit into four categories:

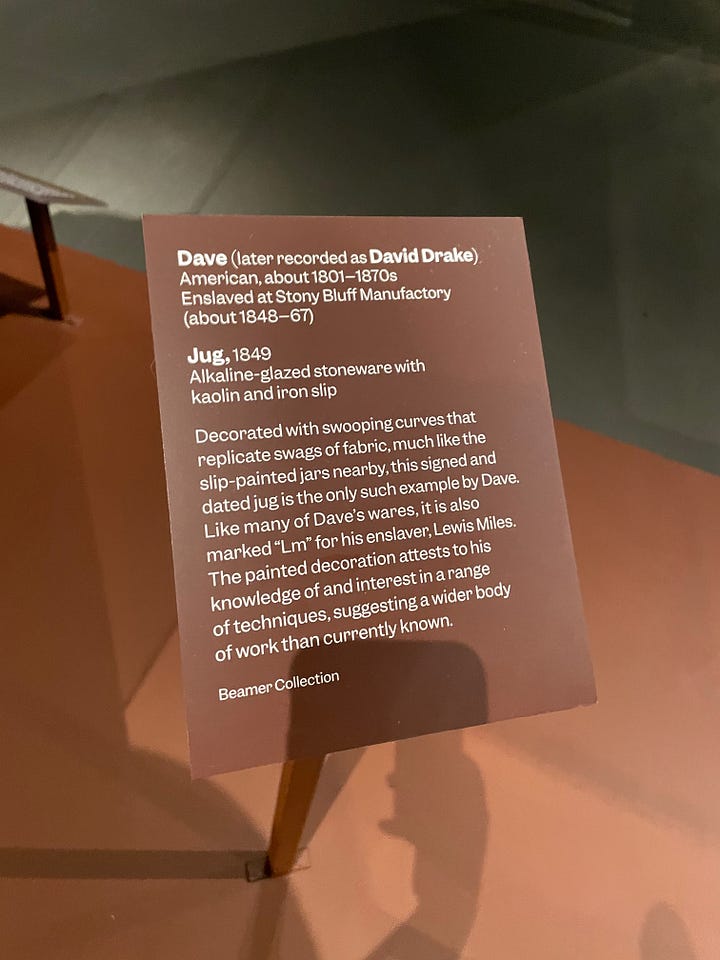

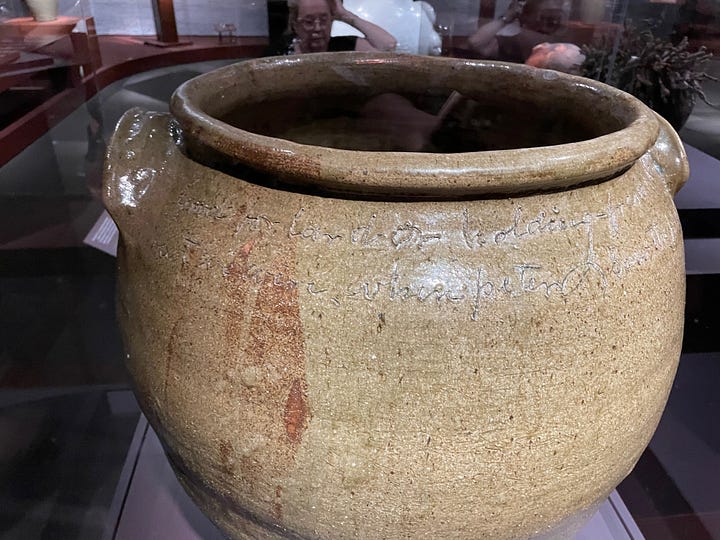

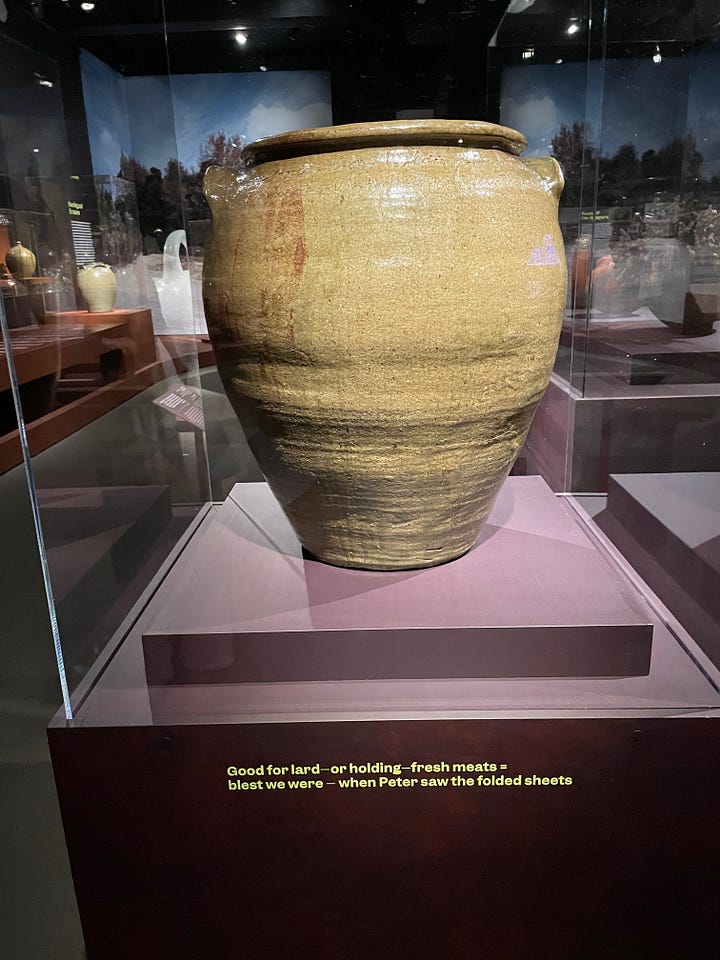

Jars that were made and signed by Dave the potter, also known as David Drake, who lived in Edgefield South Carolina in the 1800s and who signed and inscribed his enormous pots with short poems. (More about him in a minute.)

Jars and bowls and jugs made by other enslaved potters in Edgefield, whose names are not known. Or, at least, many of their names are known, but we have no way to connect the names of the individual potters to their specific works. The exhibit included a large sign that contains a partial list of names of enslaved potters from Edgefield, an attempt to rectify, somewhat the erasure of their personhood and the claiming of the work of their hands by those who enslaved them.

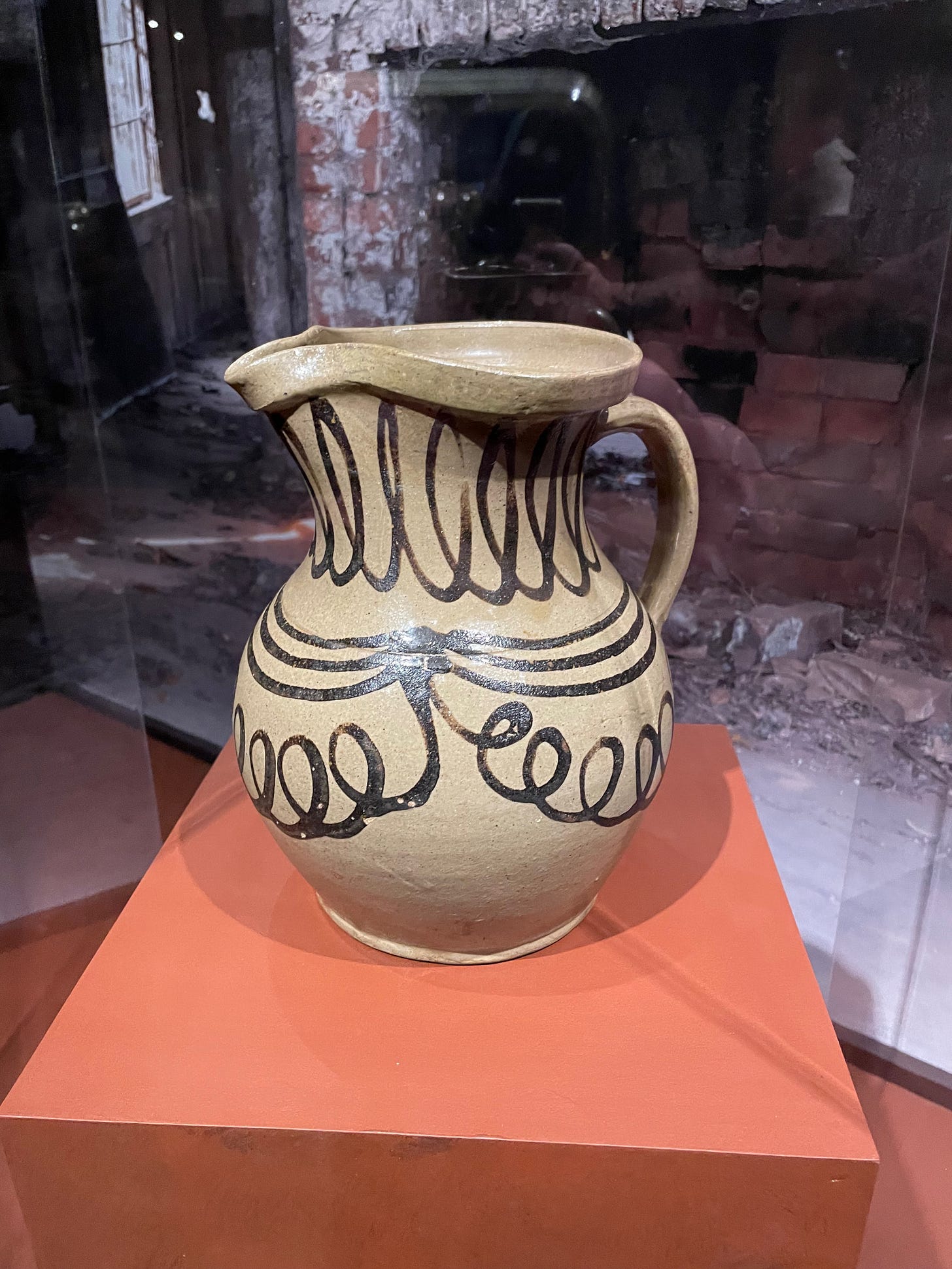

Works by African artisans from the 1800s, a reminder that many of those people who were brought to this country as slaves were artists already in their home communities and they brought their own artistic traditions with them to this country. That African tradition is partly expressed in the so-called face-jugs that were on display.

Works by present-day artists who were inspired by the work of the Edgefield potters, a continued conversation between the living and the dead, testifying to these works as part of an ongoing, still-vital tradition.

Dave the Potter and Poet

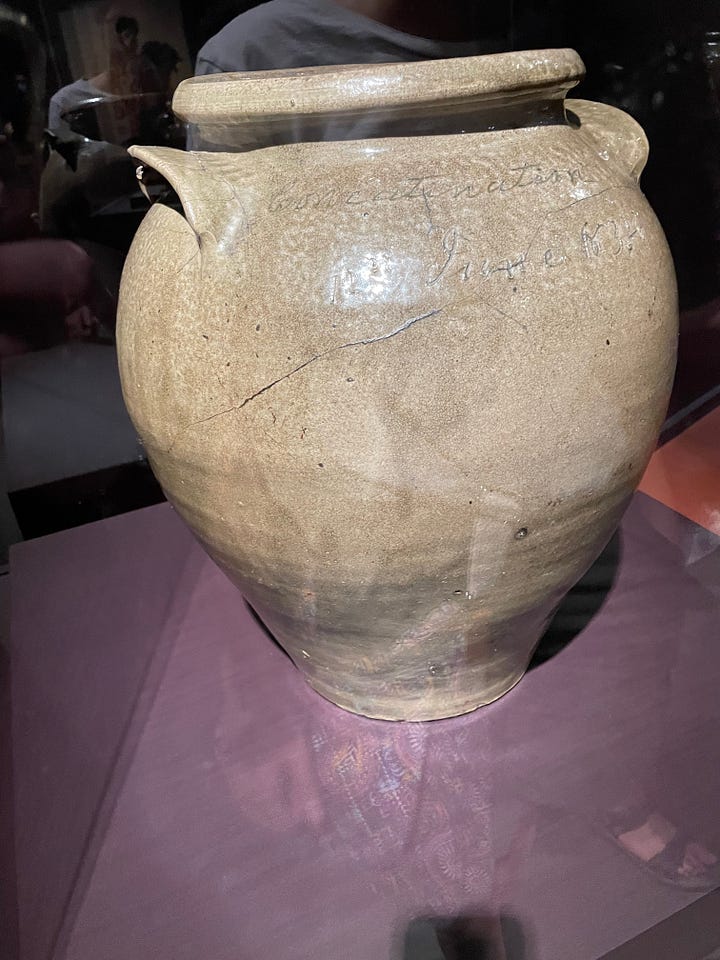

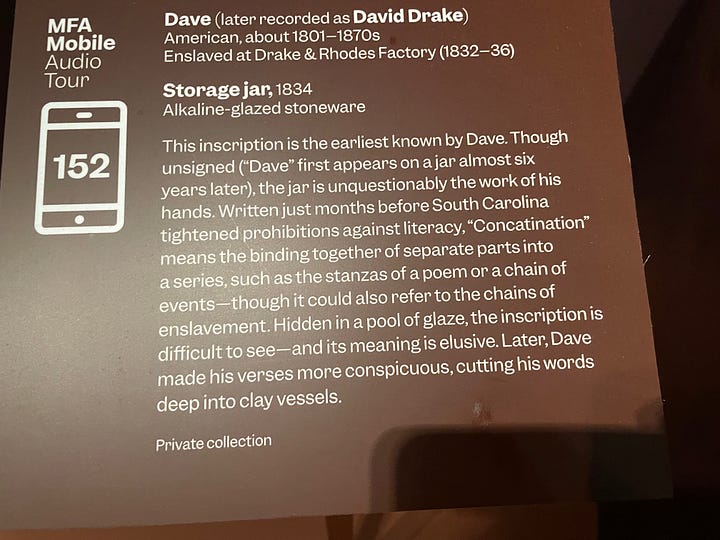

The central focus of the exhibit were the enormous stoneware jars made by David Drake, who signed his pots simply Dave. Few potters could make jars as large as his biggest pieces; to make them would take great strength and skill.

And though to the untutored eye these utilitarian vessels might not seem like incredible works of art, with their drab earth-tones and simple functionality, still, they are well-crafted, symmetrical, beautiful— the work of a true craftsman. And they have lasted for almost two hundred years.

Remarkably, Dave signed his name and dated many though not all of his pieces; which is rare for ceramics in any time and place and otherwise unknown in ceramics made by slaves. Finally, some of his jars he inscribed with short poems, rhyming couplets which testify to his wit and humor and also to his grief.

David was probably born around 1800. He took his last name from his first owner, Harvey Drake. He probably learned to read from Dr. Abner Landrum, Harvey’s uncle and business partner who likely had Dave working as a typesetter for his newspaper.

One of Dave’s poems is an epitaph for Dr Landrum:

When Noble Dr. Landrum is dead May Guardian angels visit his bed 14 April 1859

The Poetry of Resistance

The American Ceramic Society writes:

In 1834, the same year as Drake’s first inscriptions, South Carolina passed new legislation in response to Nat Turner’s Rebellion that established criminal penalties for teaching either enslaved or free people of color how to read and write. A JSTOR Daily article notes that if an enslaved person was caught reading or writing, authorities may amputate their fingers and toes.

The coincidence of Dave signing his name to his work at the same time that it was made illegal for a black man to learn to read and write makes it a marked act of resistance and rebellion. Dave didn’t sign his name and inscribe his poems because it was safe to do so, but precisely because it was not. This makes him a heroic figure.

An article in the Smithsonian notes that Dave’s agency is remarkable:

His poetic musings and the use of his signature is a coded rebuke and a resistance to the inhumane laws of enslavement, says Leslie Umberger, SAAM’s curator of folk and self-taught art.

“Drake had a job to make utilitarian vessels of a certain type, but what he made far exceeded the form,” she says. “He created more than a mere jar to hold something; he made a record of himself, his artistry, his literacy, and of the state of things in his world as they were for his people.”

I wonder where is all my relations Friendship to all - and every nation 16 August 1857

This short poem, which begins with wondering where his family are, is a quiet, coded, testimony to the cruelty of slavery. One wonders: which of Daves’s family had been sold he knows not where? Some scholars speculate it was his sister and her children, or maybe his wife and children. And yet the second line of the poem offers friendship to all, to every nation. Is that line there to mask his lament, making it seem part of a more acceptable general sentiment? Or is it evidence of a magnanimity which is almost unfathomable?

Dave’s Poems

This page from the National Humanities Center has a list of all of Dave’s known poems. There are twenty-seven all told. I wonder how many others Dave made that have since been broken or lost. We can never know everything he wrote. Poets.org, the webpage of the Academy of American Poets, also features a biography with what facts historians have been able to piece together as well as some of David Drake’s poems.

Some of Dave’s poems are relatively prosaic: describing what the jars will someday contain:

Great & noble jar hold sheep goat and bear 13 May 1859

or

A noble jar for pork or beef then carry it a round to the indian chief 9 November 1860

Some of the poems are more enigmatic:

The sun, moon and – stars in the west are plenty of – bears 29 July 1858

I love this one with the sun and moon and the star. And then I’m left pondering: Why bears? Why “in the west”? Is bear a reference to the Big Dipper, the Great Bear, the constellation that points towards North and freedom? Is it dreaming about the western frontier and unsettled lands? Is it a hyper-local warning about dangers that lurk in whatever place is immediately to the west of where Dave is?

A pretty little girl on a virge volca[n]ic mountain, how they burge 24 August 1857

My mind goes in so many directions with this one. What do you make of it?

Some of the poems have an explicitly Christian and didactic tone:

If you don’t listen at the bible you will be lost 25 March 1859

But are they expressions of Dave’s personal faith, or are they meant to appeal to the user of the jar?

I – made this Jar all of cross If you don’t repent, you will be lost 3 May 1862

This one feels explicitly Christian and yet also mysterious. What exactly is a jar made of cross? Does that refer to the toil that went into making the jar? Or prayer? Or anger? Is the final line a dire warning to slaveholders during the Civil War, warning about the sin of slave-holding? Or does it merely express a pat Christian sentiment?

(I’m sorry the following photos aren’t of higher quality. I snapped them with my phone, mostly for my own remembering.)

Samuel Hardman has an interesting commentary on this Christmas couplet, connecting it to a poem by Paul Lawrence Dunbar. The MFA tag had an alternate explanation, as I recall, theorizing that it was common to sell off slaves after Christmas.

I wonder if the line about Peter and the sheets isn’t a reference to St Peter finding the folded burial clothes in Jesus’ empty tomb on Easter Sunday.

Pottery Is Poesis

I took a ceramics class in college. We didn’t get to use a wheel— that was for more advanced students who moved on to the second semester, mostly for ceramics majors. But I am grateful for that time spent with clay in my hands, making vases and bowls and flowers because I have a bit better understanding of the process of making things out of clay. Someday I would love to take more classes, get my hands dirty, even try my hand at throwing pieces on a wheel. There is something enchanting about making things out of clay. Something divine. No wonder in the Old Testament God is often imagined as a potter and we humans as clay pieces shaped by his hands.

The Greek word “poesis,” from whence the English word “poetry” derives, means “making” and refers equally to the clay-shaping of a potter as to the word-shaping of a poet. With this in mind, I see Dave and all potters as fellow-poets, fellow-makers. But Dave stands out because he was also a shaper of words as well as a shaper of clay.

In 1819, around the time when Dave was learning to be a potter, the poet John Keats, who is about five years older than Dave, wrote his famous Ode to a Grecian Urn, in which he apostrophizes the urn itself, but spares no words for the artist whose hand made the beautiful object. Perhaps Keats did have in mind the potter as a fellow poet. I love to think that his love for the urn also encompasses a love for the maker of the urn. And no poem can be all things, yet I can’t help wish that Keats had addressed the potter rather than the urn. I love Keats’ poem and yet I find myself peering past Keats toward the urn, which I can only see through his words, and then past the urn to the unknown artisan whose skilled hands shaped the urn.

There are many books and websites where you can read about Dave the Potter. For me, the scant bits we know about him, his little bits of poems, also make it easier to imagine those other Edgefield potters whose names are not known but who also produced beautiful work.

Most pottery throughout history is unsigned. But it is a wonderful act of the imagination to try to reach out and touch them, those artists whose work continues to live long after their makers have become dirt. Now I can no longer see these or any pieces by unknown artists without wondering about the artisans who made them, the world they lived in.

If you’ve read all of this, thank you so much for reading. Please leave a comment and join in the conversation. What do you make of Dave’s poems?

““Artist once known” was first used in exhibitions featuring First Nations Art at the Art Gallery of Ontario curated by Wanda Nanibush (Beausoleil First Nation). Museums across the United States and Canada have since adopted this language to remind visitors of historical erasures often tied to violent histories of colonization, the forceful removal of Indigenous people from their lands, and the institution of slavery.”

Why do some labels say “Artist once known” at the Hood Museum of Art?

What a lovely ekphrastic poem and history lesson!!! Thank you so much for sharing Melanie!!

Excellent post! My grandparents had a piece of old pottery that I loved. It was large and heavy in a gray/green hue with a narrow spout and small handles. I believe there was a mark of some kind, but not a name. My understanding is the provenance was similar, and I appreciate the opportunity to ponder its maker and to remember my grandparent's home.