June Books

In which I finally finish The Betrothed, binge read Katherine Addison, review two collections of poetry, and start (but do not finish) too many books.

I love paintings of people reading. I took this one when we were meeting with friends at the Museum of Fine Arts on Saturday.

I would like to think this is an accurate representation of me on my recent vacation, but the truth is I only read at night in my tent. When there were rocks to be had I was sitting on them staring at the sea, not a book. Or peering into tide pools. Or taking photographs of my children and of rocks and lichen and waves.

Summer is here and while I don’t necessarily read by season, it’s definitely been a time for light reading. My brain has been skipping like a pebble across a pond. I’m having a hard time sticking to one book, as you will see in the number of books I’ve started and not finished. Nevertheless, I managed to finish a few. And I have acquired two new collections of poetry that I am very excited to tell you about.

What good books have you been reading?

First, The Betrothed: A Seventeenth Century Milanese Story Discovered and Rewritten by Alessandro Manzoni (edition revised by the author), translated by Michael F. Moore

Finally finished!!! I’ve been reading this one for months and it’s been a lovely slow, meandering journey, but it’s nice to finally have reached the conclusion, though I’m also certain tat this is a book I will want to revisit at some point.

The Betrothed (I Promessi Sposi) is a historical novel written in the 1840s but set in the 1620s. Like all 19th century historical novels, it rather sprawls. It takes detours into history and politics and in has many authorial interjections and digressions. It’s delightful.

It’s a classic of Italian literature, one of those books that all Italians are supposed to read in school. Like most classics that are wildly popular, it’s very worth reading. It’s a human story and at its heart is a contemplation of marriage as a prize worth fighting for as the two young peasant protagonists, Renzo and Lucia, are thwarted in their attempt to be married by the evil Don Rodrigo and the cowardly Don Abbondio and the sinister nun the Signora as well as by many twists and turns of fate.

It’s a very Catholic novel as well. It takes spiritual matters very seriously and earnestly. Marriage is treated as a solemn sacrament. Prayer is efficacious. There is a cowardly priest who neglects his flock— and he is rightly admonished by a good and holy bishop. There is a good Franciscan priest who does everything in his power to help the young lovers. And wickedness abounds as well because the world is a fallen place.

There are a famine and a plague. There is a Nameless evil villain who undergoes a surprising transformation. There are funny bits, sad bits, and not too many boring bits. Lucia is good and virtuous, Renzo doesn’t quite measure up to her goodness, but he grows through the novel. If you are in the mood for diving deep into something long and sweet and refreshing, you could do worse for your summer reading.

The frame narrative is that Manzoni claims to be adapting a historical manuscript (in that regard it reminds me of the novel version of The Princess Bride, and that makes me wonder if William Goldman was inspired by Manzoni). The novel begins with a long paragraph purportedly transcribed from the 17th century historical manuscript which is his source. Then Manzoni breaks off, apologizes for the style, which is long-winded and overly ornate.

He says he almost gave up on his transcription, but it's a beautiful story and he thinks people will want to read it so he's going to rewrite and correct it to something more pleasing to his readers. But then also he has to consult other period authors as well, he’s a stickler for accuracy and not relying on only one historical source. And thus the insertion of authorial comments about these sources and long historical digressions based on his additional research and all these little fact-checking side quests. Plus historical notes filling in context his 19th century readers might not know about.

Manzoni is thus poising his novel as the more-readable adaptation of an older work. He is salvaging what is worthwhile while ditching that which will be uninteresting to the reader. At time when his narrative digresses into politics or some other subject, he will interrupt himself, apologize, and get back to the main narrative. This gives a playful style to the text but allows him to infodump occasionally while blaming it on his source text. It’s not quite William Goldman’s “good parts version” of S. Morgentern’s classic, but it’s in the same vein: adventure, rogues, villains, kidnapping, swords, miracles. And a bride who is a peasant, but has also something of the princess about her.

The Chronicles of Osreth

Earlier this year The Tomb of Dragons, the third book in Katherine Addison’s Cemeteries of Amalo trilogy, was released and it finally came up in my Libby queue, so this month I’m reading it but also revisiting several books in this series. Evidently Katherine Addison has designated all the books set in the world of The Goblin Emperor as “The Chronicles of Osreth”— does that mean that world is called Osreth? I suppose it must, though I don’t remember that name coming up in any of the books. Nor could I find anywhere on her page a mention of the books under the title “Chronicles of Osreth”. (But see a cool map here, that Addison links to from her author page.)

The Tomb of Dragons (Cemeteries of Amalo trilogy book 3) by Katherine Addison. This is the third of the trilogy of spin-off books from Addison’s gorgeous novel The Goblin Emperor. This supernatural detective series follows Celehar, who is a secondary character in The Goblin Emperor. Celehar is a cleric and a Witness for the Dead. He has the supernatural power, given by Ulis, the god he serves, which allows him to read the thoughts and mental images of a dead person from the moments before they died. This gift allows him to solve mysteries; but he also has skills and contacts that make him a competent investigator. He is also able to speak to ghosts and his ability to tap into the memories of the dead gives him a tool for fighting ghouls.

I love The Goblin Emperor. It’s one of those books I keep reading over and over again. I’m not sure why, but it hits a sweet spot. I like to linger with both the protagonist and the world Addison has created. However, I don’t love the Celehar books in quite the same way. And yet I do appreciate them as explorations of the larger world that Addison has crafted so carefully. Unlike Maia who is confined to the royal palace and city, Celehar is free to roam widely and his adventures explore the judicial system and the complex religious systems and more of the mythos of their world.

I especially love the complexities of religious beliefs and burial customs. One thing that always excites me is when fantasy authors take the time to create religions that feel real and that are taken seriously by at least some of the characters. Sure, there are those who consider themselves too sophisticated to believe in the gods or pray or practice anything other than a purely social and outward observance of their beliefs, but that is how people are. And there are others like Celehar for whom religion is the most important thing, who follows his “calling” wherever it takes him. Who prays and meditates and even receives visions from his god, Ulis. But he’s also respectful towards those who follow break-away sects. Though not to those who refuse to bury their dead properly— but for the very real reason that in his world failure to observe the proper burial customs often results in the dead person’s body rising as a ghoul and praying on the dead and then the living.

I will say that by the end of Tomb of Dragons I liked Celehar much more. He’s growing into his strange role as freelancing witness working for the Archprelate. He’s making friends and connections. People like him— much to his own surprise. He’s coming out of the shell of grief and anguish he’s been stewing in and he’s becoming a much more pleasant and interesting person to be around.

Anyway, this third novel brings Celehar back to Cetho and the imperial court and has an audience with the emperor. It’s a small incident in the plot and it doesn’t feel like nearly enough for those of us who really want another Maia story, but it is still really good to return to the anchor point.

Moreover, I liked the mystery plot in this story where Celehar is petitioned to witness for dragons. I don’t think we knew previously that this world has dragons! (One friend of mine complained that The Goblin Emperor feels more like steampunk than fantasy, but I think these later books have a bit more of the fantasy elements which are present but subdued in that novel.

There’s a definite shift as Celehar steps away from the role of witness for the dead for the city of Amalo and into a different role. This winds up the trilogy with a suggestion that if there are more Celehar books, they will be set in a different location and have a different set of characters or concerns. (Or maybe there won’t be any more books. Perhaps— I hope not!— this is goodbye?)

The Witness for the Dead (Cemeteries of Amalo trilogy book 1) by Katherine Addison.

Reading The Tomb of Dragons, I realized I was having a hard time remembering the first two books, what had happened, and especially who the various characters were. So I got the audiobook of Witness for the Dead, the first book in the series and listened to it while doing chores and packing for vacation.

This first book of the trilogy starts not long after Celehar has arrived at Amalo. We discover this new city through his eyes and meet many new people. It’s a murder mystery with several different mysteries to be unraveled: a missing wife, a drowned body, a contested will. There are also a ghoul to quell and a trial by ordeal to be endured, an airship crash to investigate, and a separated father and daughter to be reunited. We are introduced to the bitter local politics of the various religious hierarchies and the cemeteries that seem to be their primary concern, the dramatic world of the opera, and the Vigilant Brotherhood, the religious order who serve as the equivalent of the city watch.

One thing I noticed and loved this time through is that about halfway through the novel Celehar stops to rehearse the facts of the case, to recall everything he knows so far. I know many careful readers with good memory would find this redundant and boring, but I greatly appreciated this mini-refresher that helped me to remember who everyone is and how the case is going. I think more mystery writers should have similar refreshers. But it also works because it’s a good character moment: Celehar is a careful investigator and he’s trying to keep everything straight in his head to he can faithfully report it

Since I was listening to this book to try to get a handle on who is who in the third book, I noticed that even in the first book there is a huge cast of characters. I desperately wanted a list. It seems to me it used to be more common, especially in genre fiction with large casts of characters, to have a list of dramatic personae at the beginning of the book. Perhaps the print versions of these books did have character lists, it’s been too long since I had them out from the library and I don’t recall. I greatly appreciate a well-written list for when my head starts spinning and I forget who everyone is. Those these wouldn’t be much help in the audiobook format. Fortunately, I found a good Wiki online and could look up characters when I got too confused.

The Grief of Stones (Cemeteries of Amalo trilogy book 2) by Katherine Addison.

I also went on to re-read the second book in the series in audiobook form. It’s a weird back to front way of reading, especially reading the ebook of the third book in the series simultaneously with the audiobooks of the first two volumes. But somehow my brain kept it all straight. More or less. Again, the little recaps Addison includes help to keep me oriented in the story. I feel like there was another series I was re-reading recently where the author kind of assumed you’d just finished the previous book and didn’t catch you up or remind you who was who and it was extremely vexatious.

In The Grief of Stones Celehar gets a female apprentice and I quite like seeing him taking on that mentor role. The cases they work— the death of a marquessa are less interesting to me than the unfolding of Celehar’s relationships with his various friends. I did like the exploration of photography and how it’s viewed in this society. Another reminder that the technology level is basically Victorian. This is fantasy elven steampunk.

The Orb of Cairado

This is a stand-alone novella in the same world as The Goblin Emperor and the Tombs of Amalo series, The Orb of Cairado has as its protagonist a scholar, the historian Ulcetha Zhorvena. Ulcetha is a scholar second class who has been kicked out of the university under suspicion of having stolen an artifact. He is innocent of the theft, but when his best friend dies in the crash of the Wisdom of Choharo airship, he leaves a trail of clues that leads Ulcetha to the artifact, which in proper treasure-hunt fashion turns out to be a key leading to another, even more important artifact.

This story also becomes a murder mystery as well as a quest for a buried treasure. I quite enjoyed it and I would like to see more of Ulcetha in the future.

Two New Poetry Books!

The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms by Mark Strand and Eavan Boland. I have plenty of poetry anthologies and I understand poetic form well enough , even if I don’t feel very bold about writing in it. But when I saw this anthology on sale I just had to have it. I love Eavan Boland. She’s one of the poets I studied in my graduate studies in Irish literature. And while I don’t know Mark Strand as well, I feel like I want to know him better. Their introductory essays and notes are excellent and the selections of poems is really quite good.

This is a book which emphasizes a hermeneutic of continuity rather than a hermeneutic of rupture. That is, it sees modern free verse forms as an extension of a conversation, not a wholesale rejection of all that has gone before. As a poetry reader and a poet who has one foot firmly planted in formalism and one firmly planted in free verse, this is a collection and an argument that appeals to me very much. I think Boland and Strand have hit the perfect note and found the perfect balance.

They set themselves the challenging rule of including only one poem from any given poet. Which means this collection is broad in scope. The sections of formal verse include modern examples as well as historical ones, examples of poets playing with the form as well as of poets cleaving closely to the form. This is a collection that loves formal poetry and also poetry that is playful when it comes to form.

In order to provide some answers, we have gone back to the exuberant history of forms, have drawn them out of their shadows in French harvest fields and small Italian courts and have laid out as clearly as possible their often turbulent passage across centuries. We hope the reader will be enchanted, as we have been, by the compelling witness of poet after poet discovering and unfolding their inner world through outward customs and cadences. We hope the reader will agree that these forms are— as we believe— not locks, but keys.

When poetic form is seen as a dialogue, the arguments for or against modernism, for or against formalism, for or against tradition enter a more coherent context. Poetry is shown to be, as it always has been, a process as well as a product. A great part of that process is the poet’s interior conversation with a possessed and dispossessed formal past, and also with a great exterior discourse. When the poem is finished, the dialogue continues— enriched by that poem, but still restless and incomplete.

Part One is Verse Forms: villanelle, sestina, pantoum, sonnet, ballad, blank verse, heroic couplet, stanza.

Part Two is a brief (3 pages) introduction to Meter.

Part Three Shaping Forms: Elegy, Pastoral, Ode.

Part Four Open Forms. (aka Free Verse— though that is not the term the authors choose to use)

It is the contention of this book that, however understandable their confusion and discomfort, the disjunction was not a disjunction: It was a dialogue in disguise. The powerful fractures of form and convention that the modernist poets initiated in the second decade of the twentieth century were not wilful abandonments of what had gone before. They were in face a passionate dialogue with it.

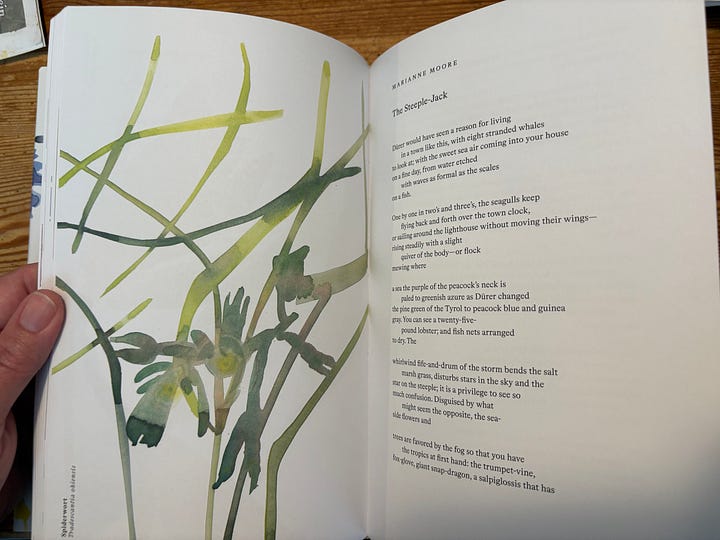

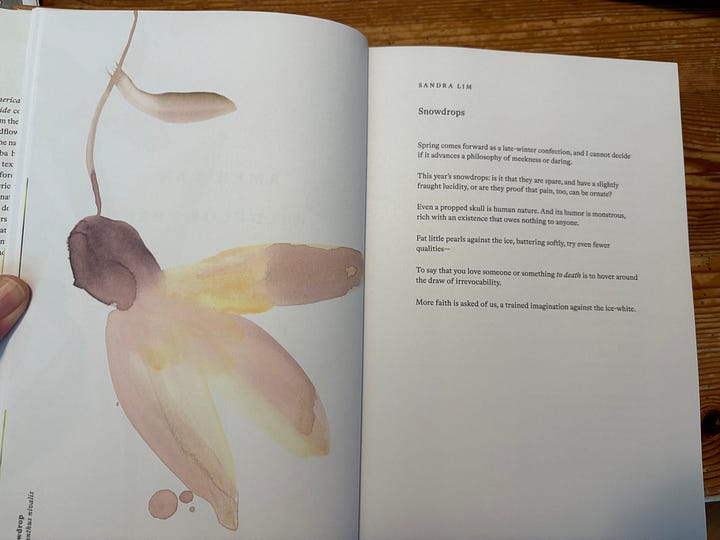

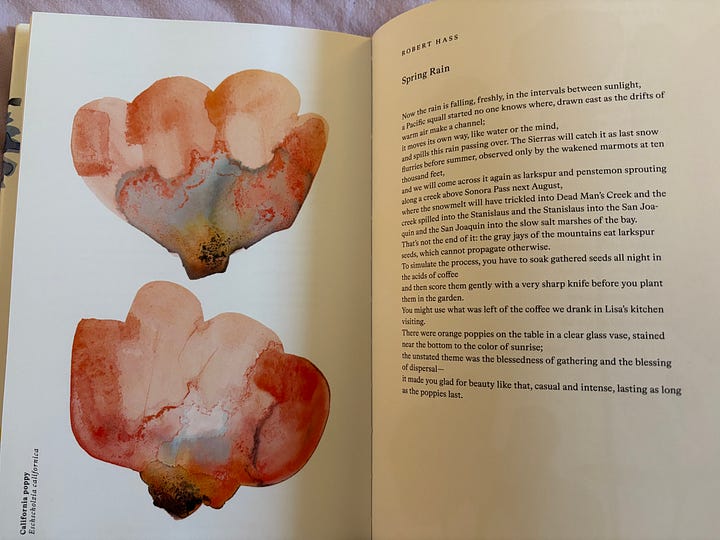

American Wildflowers: A Literary Field Guide edited and with an introduction by Susan Barba, illustrated by Leanne Shapton.

I found this gorgeous anthology at a bookshop in Bar Harbor, Maine and absolutely had to buy it. (I took pictures of many other books I wanted to buy, but restrained myself to making notes so I can buy them later.) It’s a collection of poems, letters, essays and other nonfiction pieces from the 1700s to the present day. Its beautiful watercolor illustrations are inspired by pressed flowers. And is organized like a field guide by species and botanical family, but using common names.

I like an anthology that has enough familiar names that I feel I can trust the judgement of the editor but enough unfamiliar names that I know I will find new friends. The poems included many by poets I recognize like William Carlos Williams, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Richard Wilbur, Jericho Brown, Denise Levertov, Robert Hayden, Ross Gay, Wallace Stevens, Li-Young Lee, W.S. Merwin, T.S. Eliot, Rita Dove, Robert Frost, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Elizabeth Bishop, Lucille Clifton, Robert Hass, as well as many I don’t know as well. And there are prose pieces by Herman Melville, Merriweather Lewis, Joseph Bruchac, and Henry David Thoreau, and many others I don’t know.

I love good nature writing and I have loved collecting wildflowers and learning their names and habits since I was in my teens and did a wildflower portfolio for my biology class. This anthology is the perfect kind of nature writing: science and literature meeting, holding hands, and rambling through the meadows and mountains. It’s been a perfect book for bringing to waiting rooms during children’s appointments or to browse through at lunch time.

Books in Progress

Chatterton Square by E.H. Young, a 1947 novel about two families in London in the time leading up to the Second World War. I might be reading this too slowly, dipping into it between other books, because I keep forgetting who various characters are. I suspect it’s a book that would be better read in one gulp, a summer read for vacation when I’m not juggling a bunch of books. It’s good, but I am not doing it justice, poor thing. I shall probably have to come back to it again later to really give it a fair shot. I’m still trying to figure out exactly what Young is doing because I keep expecting the novel to be one thing and then it seems to actually be something else entirely.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. I haven’t re-read this classic since I first encountered it in high school, and it feels like it’s about time. My oldest daughter really enjoyed it when she read it last year and I remember it as depressing in content but gorgeous in style. And so far that impression is being borne out. It’s a beautifully written novel. And its worldview is so so bleak. So much loneliness and boredom and yearning and deception and so little that is good and beautiful and true. It is a classic because it tells the truth and it tells it well; but it’s a classic that holds up a mirror to a side of America that I cannot love.

Truth be told I’m having a hard time picking it up. I want to read it, or at least I want to have read it, but when it comes down to it, I don’t really want to be reading it right now. To me Gatsby feels less like a light summer book and more like a book to read on a cold winter day when I want that breath of summer which the book holds carefully between its pages.

Thoughts from Nyokodō by Takashi Paul Nagai, the Japanese scientist, Catholic convert, and survivor of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki whose story is told in A Song for Nagasaki by Paul Glynn (which I’m currently reading with my second daughter.)

This is the final autobiographical book Nagai wrote, published posthumously by his friends. By the time he wrote this book he was dying of radiation-induced cancer and the sections are short and episodic. Nyokodō was the small hermitage that was built for Nagai by his friends so that he could have (relative) peace to write his books. He was constantly interrupted by the stream of visitors who came to see this great scientist and apostle of peace.

Nyokodō means love of self and refers to the commandment of Jesus: to love your neighbor as yourself. The choice of name is fascinating to me coming from an American Catholic context where would likely want to downplay the love of self part and emphasize love of neighbor.

Kingfisher by Patricia McKillop

So far this one seems to be a retelling of the Arthurian legends of the Fisher King and the quest for the grail; but transposed to a modern world that is definitely not England— but also kind of is— with cars and electricity and also with sorcerers and werewolves and pagan deities. The characters seem to be lost in a kind of dreaming, having forgotten who they truly are and what story they are in. It’s fun to recognize the outlines of familiar stories in unfamiliar places and names and to puzzle out which legends are surfacing from the mists. I’m about a third of the way through the book and curious to see how it will all come together.

Wow Melanie you are an ambitious reader. I am only reading one book this summer Is A River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane. I’m enjoying it immensely. The poetic form book you mentioned sounds worth adding to my summer reading list though. And maybe I’ll be brave enough to try The Betrothed. Thank you for sharing your reading list.

The Betrothed was on sale for Kindle recently, and I passed it up! Argh! The Making of a Poem sounds like what I've been looking for for poetry instruction. I'm still behind with posting and commenting after going on vacation, and you are publishing up a storm! I'm so impressed!